Personal Note

Game AI is something I find fascinating, my mind going into many directions just thinking about it:

- How is Stockfish able to accurately evaluate positions, pick moves and think so far ahead?

- How are my CPU opponents in Gran Turismo able to race so cleanly and adapt their lines to whatever situation appears on the track?

- How are the individual players in FIFA or Madden able to realistically coordinate on the field and adapt their tactics?

- Why do Arma’s CPU units feel so stupid? (Spoiler: It’s extremely difficult to write good computer controlled units for a game like this, especially without impacting performance.)

- And there are many more questions like these. I can’t possibly write them all down here.

In this series of blog posts I’ll be sharing my experience as I journey into writing game agent logic and AI. You can follow along, hopefully learning from my insights and mistakes alike. I’m coming from a background in software engineering, so data structure and algorithm knowledge is a must for following this series.

The tic-tac-toe interface

Before I go into making agents, I need to be able to play the game. I could try finding some pypi package, but tic-tac-toe is simple enough to quickly code on my own. In this post I’ll only show the interface, because its most relevant for the agent later. If you want to see the full code, it’s available here. I’ll be using Python here, but the logic will be the same for any language of choice.

The board

The board is responsible for storing the played moves, showing available moves, showing the winner in a given position, and providing a quick string display. The interface looks as follows:

class TicTacToeBoard:

def __init__(self, board_override: list[list[str]] | None = None) -> None:

...

def get_winner(self) -> str | None:

...

def get_valid_moves(self) -> list[tuple[int, int]]:

...

def play_move(self, side: str, pos: tuple[int, int]) -> None:

...

def get_board_copy(self) -> list[list[str]]:

...

The game

The game is responsible for keeping track of players and turns:

class Game:

# passing a None agent will result in player turns

# Agent is an ABC for the different agents that will be developed later

def __init__(self, agentx: Agent | None, agento: Agent | None) -> None:

...

# loops through each turn until a terminal state is reached

# returns the side that won, or None if draw

def game_loop(self) -> str | None:

...

# This method specifically handles human user input if needed

# It's used inside game_loop()

def _get_player_move_input(self, side: str) -> tuple[int, int]:

...

Note: each game has its own board instance.

Agent interface

Now that the game is ready, a standard interface is needed for whatever types of agents we would like to make. This would allow us to easily switch between them later:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from TicTacToeBoard import TicTacToeBoard

class Agent(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def get_best_move(self, tttb: TicTacToeBoard) -> tuple[int, int]:

...

The agent’s purpose is to return the best move in a given board position.

The random move agent

A random move agent can be made so the game can be played and tested.

class RandomAgent(Agent):

def get_best_move(self, tttb: TicTacToeBoard) -> tuple[int, int]:

return random.choice(tttb.get_valid_moves())

This allows us to play the game now!

from Game import Game

from agents.RandomAgent import RandomAgent

if __name__ == "__main__":

game = Game(agentx=None, agento=RandomAgent())

winner = game.game_loop()

if winner is None:

print("The game is a draw")

else:

print("The winner is:", winner)

input()

The minimax agent

I’ll use the minimax algorithm to make an agent that can select its next move by evaluating possible future positions. But before that, I’ll need to know how to evaluate if a position is good or bad. For this I’ll use heuristics.

Heuristics

Heuristics are oversimplified rules for making quick decisions. They’re based on experience and intuition and don’t rely on a logical or scientific system. This is simple and good enough for tic-tac-toe. I’ll use my personal experience with the game to think of patterns on the board that can be evaluated as advantageous for either side.

A simple rule can be that if a side can place 2 marks in a row, column or a diagonal, without being opposed, it gains 1 point for each. Another rule can be that when a side completes a win, it evaluates as 100 points. In summary it’s as follows:

| Side | Rule | Points |

|---|---|---|

| x | Place 2 marks in a row, column or a diagonal, without being opposed | 1 |

| x | Place 3 marks in a row, column or a diagonal | 100 |

| o | Place 2 marks in a row, column or a diagonal, without being opposed | -1 |

| o | Place 3 marks in a row, column or a diagonal | -100 |

Examples

This position evaluates to

-1

This position evaluates to

1

This position evaluates to

2

This position evaluates to

99

Implementation

Written in code, our heuristics would look like this:

class Heuristics():

@staticmethod

def get_counter_eval(counter: Counter[str]) -> int:

if counter["x"] == 2 and counter["o"] == 0:

return 1

if counter["o"] == 2 and counter["x"] == 0:

return -1

if counter["x"] == 3:

return 100

if counter["o"] == 3:

return -100

return 0

@staticmethod

def get_board_eval(tttb: TicTacToeBoard) -> int:

board = tttb.get_board_copy()

combinations: list[list[str]] = []

combinations.append([board[i][i] for i in range(3)])

combinations.append([board[2-i][i] for i in range(3)])

for i in range(3):

combinations.append([board[i][j] for j in range(3)])

combinations.append([board[j][i] for j in range(3)])

res = sum(

Heuristics.get_counter_eval(

Counter(combination)

)

for combination in combinations

)

return res

Minimax Algorithm

Now that I can evaluate board positions, I have what I need to search for a good move. To find it I’ll use the minimax algorithm.

Where you maximize your minimum evaluation gain at the end of the sequence.

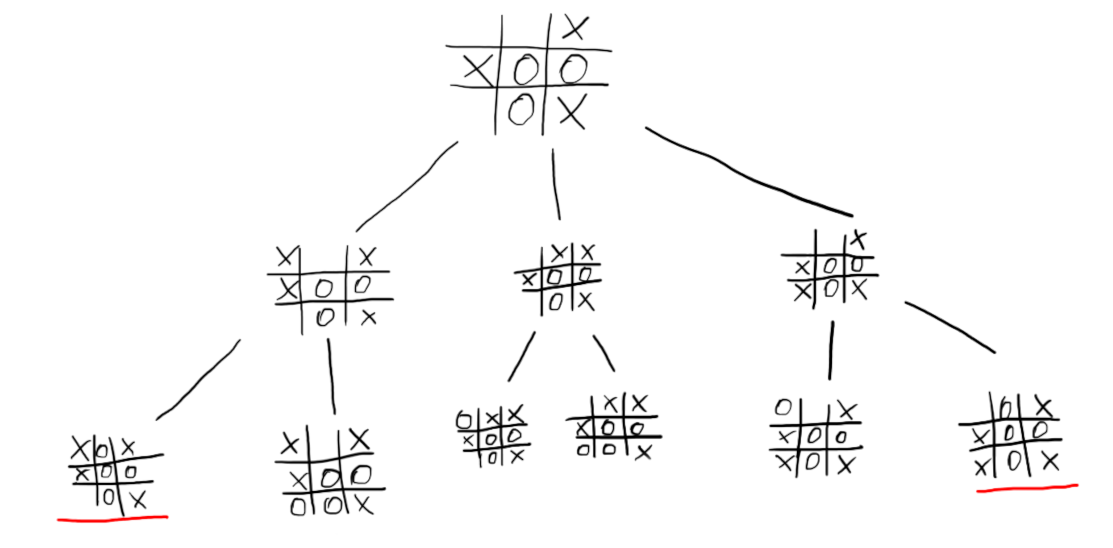

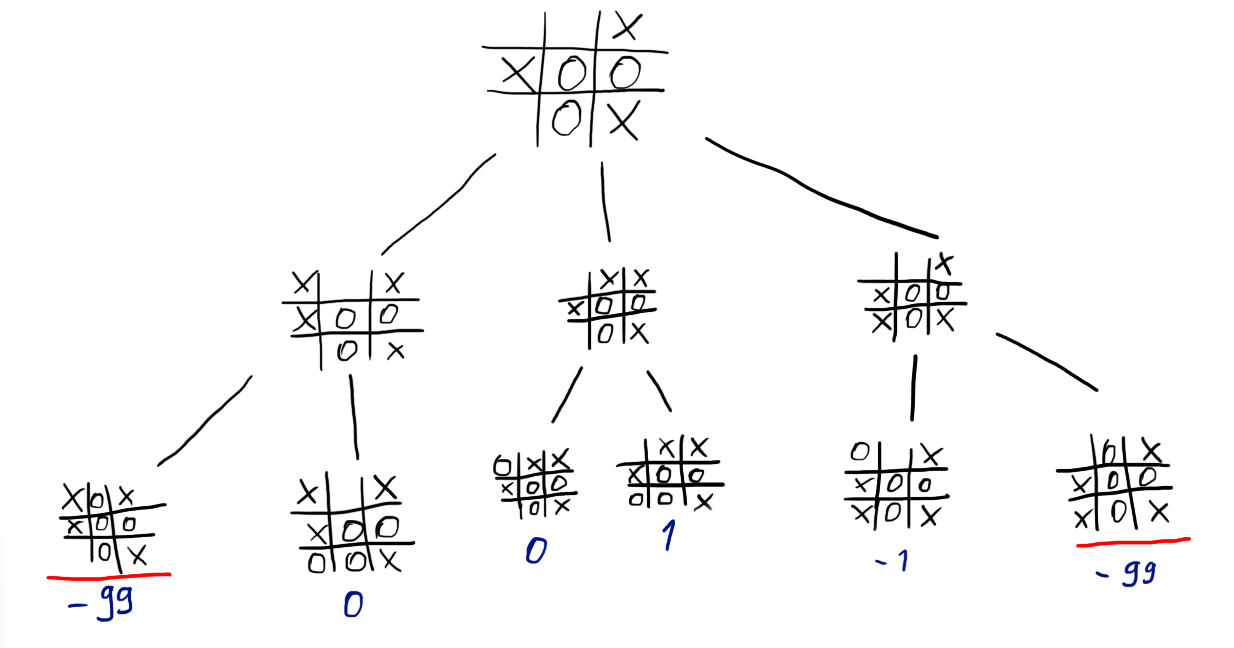

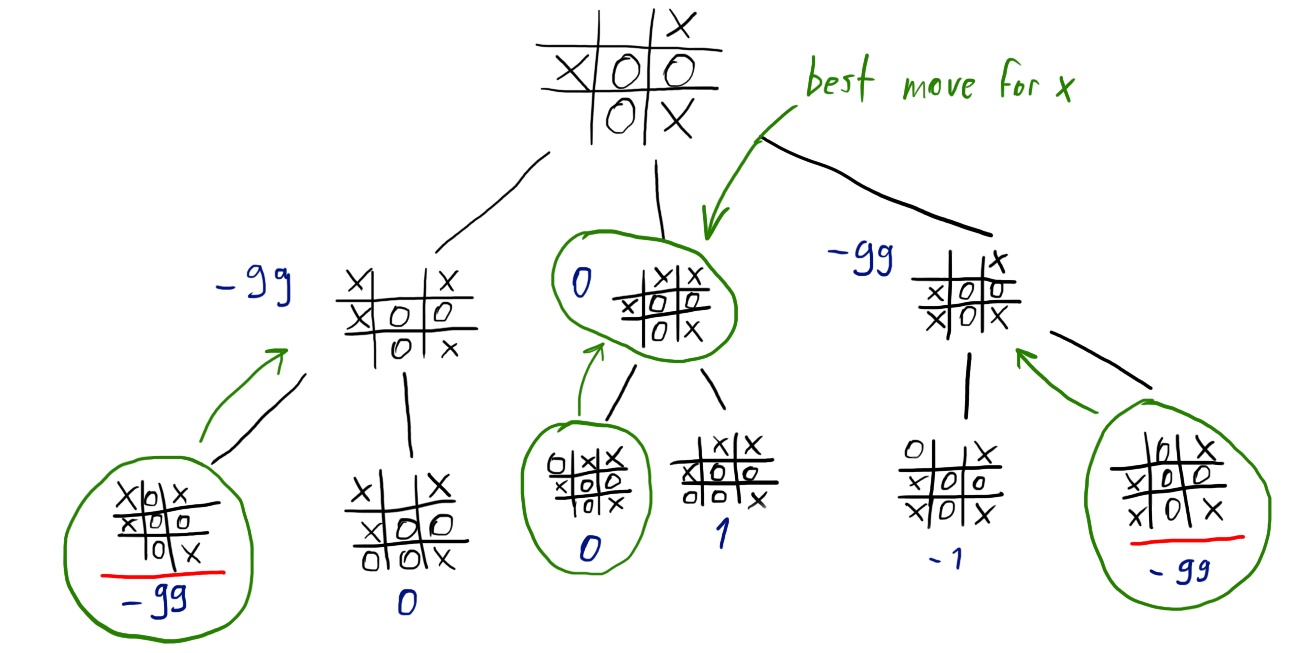

Thinking 2 moves ahead

An intuitive example of a minimax with a depth of 2.

Consider the tic-tac-toe position above. It’s x’s turn to make a move.

An n-depth tree can be made for all possible n-moves ahead. In this example, the depth is 2. There are two leaves underlined in red, these are terminal states of the game, where “o” has won.

We can now use our heuristics to evaluate each leaf position. We now have numbers that show 2 of the 3 next possible moves for “x” result in a loss if “o” plays the best move afterwards.

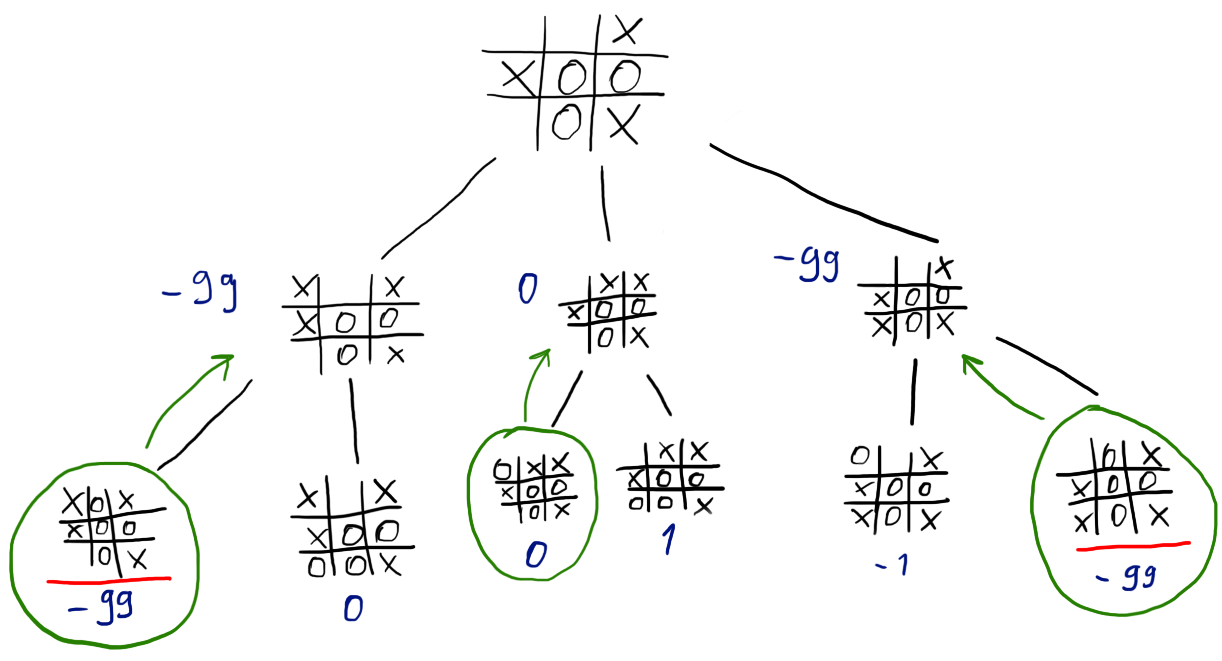

For each of x’s next possible moves, we can get the minimum possible evaluation resulting from o’s move afterwards, and assign it x’s move nodes in the tree.

From each of x’s depth 1 nodes, we can now get the maximum possible eval. This should be x’s best move, thinking 2 steps ahead. Using this approach we maximize our minimum possible evaluation.

Thinking 4 moves ahead

On the previous example, the nodes with a depth of 1 picked the move with minimum value of their children, and the root picked the move with maximum value. This idea can be extended to an n-depth tree, where each for each node:

- if at an odd depth, picks the minimum value child

- if at an even depth, picks the max value child

This alternating pattern is at the core of the minimax algorithm. Each layer of the tree expresses an agent that tries to get the best evaluation for their side.

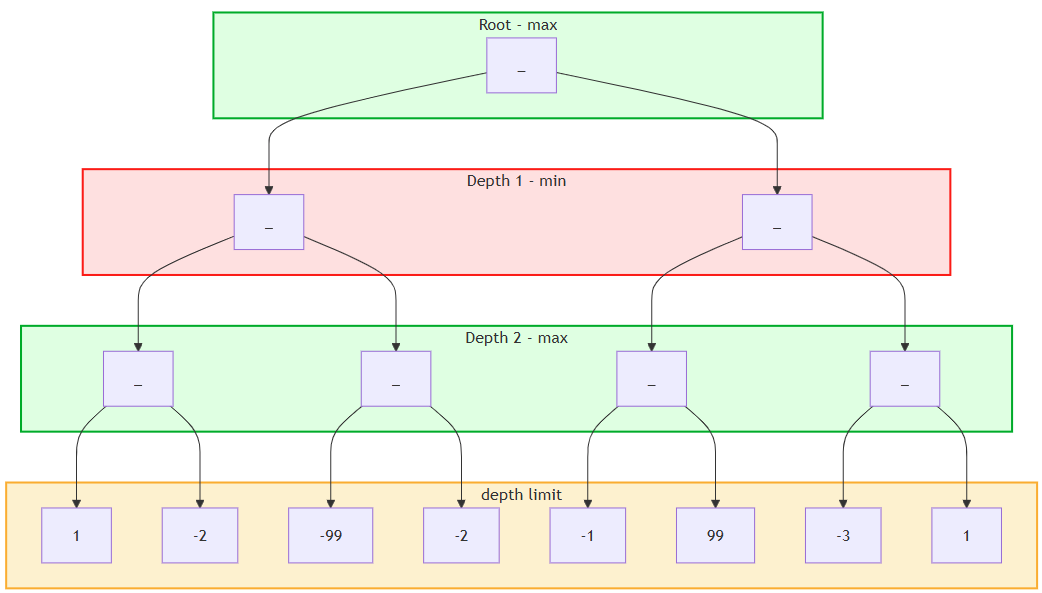

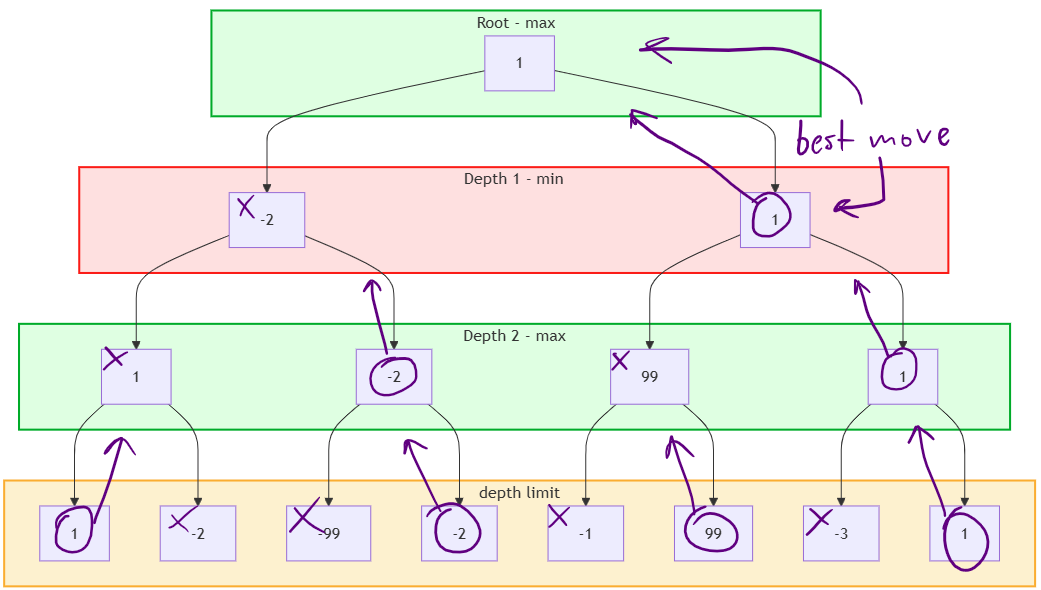

For an example with calculating 4 moves ahead we can think of an abstract game, where on each turn a player can make two choices.

The resulting tree with a depth limit of 4 will look like this. The final reached position on each leaf node is evaluated.

Each layer recursively picks either the min or the max score child, depending its side. We can now see the move that maximizes the minimum gain.

Writing tests before the implementation

Now that we have some intuitive understanding of how the algorithm works, we can begin by writing some tests for scenarios where we expect the agent to make the right move.

First, we make an obviously wrong version of our agent, implementing the Agent base class:

class MinimaxAgent(Agent):

def get_best_move(self, tttb: TicTacToeBoard) -> tuple[int, int]:

return (0,0)

Now we can think of some example positions and write tests about the best expected move:

class TestMinimaxAgent:

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"position, side, expected_result",

[

(

# The given position

[["_", "_", "x"],

["x", "o", "o"],

["_", "o", "x"]],

"x", # The side that plays

(0,1) # Coordinates of the best move

),

(

[["x", "_", "_"],

["_", "o", "_"],

["x", "_", "_"]],

"o",

(1,0)

)

]

)

def test_best_move(

self,

position: list[list[str]] | None,

side: str,

expected_result: tuple[int, int]

) -> None:

tttb = TicTacToeBoard(position)

minimax_agent = MinimaxAgent()

agent_move = minimax_agent.get_best_move(tttb)

assert agent_move == expected_result

Our agent returns hard-coded (0,0). That’s fine. Now that we have failing tests, we can quickly write the implementation and consistently test it. There are more example test cases in the repository.

Implementation

The algorithm is essentially a DFS, where each subsequent recursive call alternates between returning the minimum and maximum value of its children. The value starts propagating from the leaf nodes. A leaf node is reached either if the game reaches a terminal state or if the depth limit is hit.

As a python method as part of our MinimaxAgent class, it would look like this.

def _minimax(

self,

tttb: TicTacToeBoard,

depth: int,

maximizingPlayer: bool

) -> tuple[tuple[int,int], int]:

# Check game terminal state or if the depth limit is reached

# Essentially checks if this node in the tree is a leaf

valid_moves = tttb.get_valid_moves()

if depth == 0 or tttb.get_winner() is not None or len(valid_moves) == 0:

return (-1,-1), Heuristics.get_board_eval(tttb)

# Logic for the node that gets the max evaluation from of its children

best_move = (-1,-1)

if maximizingPlayer:

max_value = -1000

for move in valid_moves:

new_board = TicTacToeBoard(tttb.get_board_copy())

new_board.play_move("x", move)

_, move_value = self._minimax(new_board, depth-1, False)

if move_value > max_value:

max_value = move_value

best_move = move

return best_move, max_value

# Logic for the node that gets the minimum evaluation from its children

else:

min_value = 1000

for move in valid_moves:

new_board = TicTacToeBoard(tttb.get_board_copy())

new_board.play_move("o", move)

_, move_value = self._minimax(new_board, depth-1, True)

if move_value < min_value:

min_value = move_value

best_move = move

return best_move, min_value

This method returns a tuple containing the best move and the evaluation for it.

We can now refactor our __init__ and get_best_move as follows:

class MinimaxAgent(Agent):

maximizingPlayer: bool

depth: int

side: str

def __init__(self, side: str, depth: int = 3) -> None:

self.side = side

self.depth = depth

if side == "x":

self.maximizingPlayer = True

else:

self.maximizingPlayer = False

def get_best_move(self, tttb: TicTacToeBoard) -> tuple[int, int]:

best_move, _ = self._minimax(tttb, self.depth, self.maximizingPlayer)

return best_move

Running the tests should now show that the agent plays correct moves every time.

Additional Sources

- https://gitlab.com/mitk0100/tic-tac-toe-minimax-and-heuristics - My GitLab repository for this project.

- https://cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/courses/soco/projects/2003-04/intelligent-search/minimax.html - Interesting read on search algorithms.